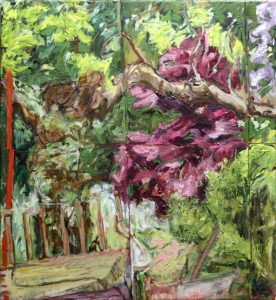

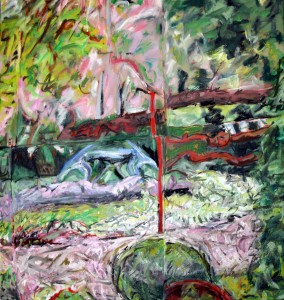

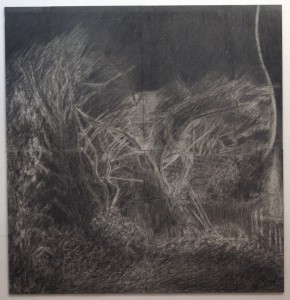

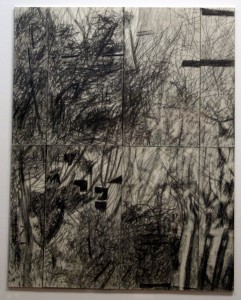

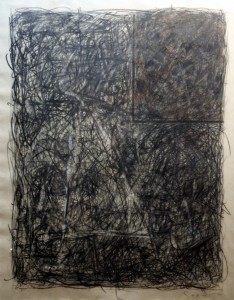

As the title suggests, the starting point for the paintings in Through the…Regency Window was the view of the garden through the windows of my early-19th-century cottage in Suffolk. The depiction of the greenery, and various objects like garden chairs and metal plant stands, is semi-figurative, tending to abstraction. In addition, the window bars are minimised to the point of near-disappearance; the effect is of a barely felt division of the picture plane.

On the one hand the paintings are intended as straightforwardly beautiful studies of a natural (or semi-natural) subject. The subliminal presence of the window bars, however, introduces an element of greater ambiguity. The division of each painting into subtly separate panels serves, at once, as a framing device, drawing the viewer’s attention beyond the literal subject matter to the act of perceiving it, and, by gently distorting the image, furnishes the “slight…almost invisible twist” identified by the writer Isaac Babel as the artist’s “secret” means of encouraging us to look at things afresh.

Furthermore, the window has a long legacy of significance in Western art, from the halo-like source of light behind the Christ figure in Leonardo’s Last Supper, to the open shutters dividing ‘Mr and Mrs Clark’ in David Hockney’s double-portrait. A source, as Christopher Masters argues, of both physical and spiritual illumination, the window also stands as a figure for our separation from the objects of our desire. My hope for Through the…Regency Window is that the paintings might resolve such tensions to capture a moment of stillness, of quiet timelessness, “the pause,” as Philip Guston puts it, “that promises future conditions.”